Cryptography

Note: Email me if you have questions.

Objective

This section will attempt to teach you how to use cryptography (colloquially referred to as "crypto") correctly. The target audience is primarily software developers, not system administrators nor operations staff.

Specifically, it will teach you:

- What functionality various cryptographic primitives can provide and when the use of them is appropriate.

- What cipher modes are and understanding their various strengths and weaknesses.

- About encryption padding schemes and where and how to use them.

- About the basics about cryptographic key management.

- How to avoid common errors when using cryptography.

It will not attempt to cover: [1]

- How to break cryptography (i.e., cryptanalysis), but will point out the properties and limitations of the cryptographic tools, and the dangers to watch out for

- How to design or implement cryptographic algorithms or cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generators. Moreover, it discourages you from doing so yourself.

- PKI and X.509 certificates

- Configuration issues for point-to-point encryption involving SSL/TLS configuration, SSH configuration, or IPSec configuration.

- Cryptographic protocols

Platforms Affected

All Relevant COBIT Topics

- DS5.8 – Cryptographic Key Management

Glossary of Cryptographic Terms

Like most specialized technical areas, cryptography has its own specific jargon. Rather than trying to define each term as it is used and cause possible distractions for those with familiarity with these terms, we will refer you to the definitions in the following glossaries:

- http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2013/NIST.IR.7298r2.pdf

- http://www.cryptomuseum.com/crypto/glossary.htm

- http://www.ciphersbyritter.com/GLOSSARY.HTM

There are also more general Internet security glossaries here:

Description

Uses of Cryptography

Initially primarily restricted to the military and the realm of academia, cryptography has become ubiquitous thanks to the Internet. Common every day uses of cryptography include mobile phones, passwords, SSL VPNs, smart cards, and DVDs. Cryptography has permeated through everyday life, and is heavily used by many web applications.

Cryptography (aka, crypto) is one of the more advanced topics of information security, and one whose understanding requires the most schooling and experience. It is difficult to get right because there are many approaches to encryption, each with advantages and disadvantages that need to be thoroughly understood by web solution architects and developers.

The proper and accurate implementation of cryptography is extremely critical to its efficacy. A small mistake in configuration or coding will result in removing most of the protection and rending the crypto implementation useless.

A good understanding of crypto is required to be able to discern between solid products and snake oil. The inherent complexity of crypto makes it easy to fall for fantastic claims from vendors about their product. Typically, these are "a breakthrough in cryptography" or "unbreakable" or provide "military grade" security. If a vendor says "trust us, we have had experts look at this," chances are they weren't experts!

Confidentiality

For the purposes of this OWASP Development Guide, we define "confidentiality" as "no unauthorized disclosure of information". Cryptography addresses this via encryption of either the data at rest or data en transit by protecting the information from all who do not hold the decryption key. We also use cryptographic hashes (i.e., secure, one way hashes) to prevent passwords from disclosure.

Authentication

Authentication is the process of verifying a claim that a subject is who it says it is via some provided corroborating evidence. We use cryptography for authentication in several different ways. First, we use crypto to protect the provided corroborating evidence (e.g., hashing of passwords for subsequent storage as we just mentioned). Secondly, authentication protocols (e.g., challenge-response protocols, such as MS-CHAPv2) often use cryptography to either directly authenticate entities or to exchange credentials in a secure manner. Finally, cryptography is frequently used to verify the identity one or both parties in exchanging messages. Such is the case when cryptography is used with Transport Layer Security (TLS) and its predecessor, Secure Socket Layer (SSL).

Integrity

We define "integrity" as ensuring that even authorized users have performed no accidental or malicious alternation of information. Cryptography can be used to prevent tampering by means of Message Authentication Codes (MACs) or Digital Signatures, both which will be discussed later. When you hear the term "message authenticity" being referred to, it is really referring to integrity. It sometimes is referred to as "authenticated encryption" as well, although in the case of symmetric encryption and shared keys, it really doesn't authenticate the sending party per se. (However, if asymmetric encryption is used, one can in fact use it to authenticate the sender.)

Non-repudiation

Non-repudiation comes in two flavors...non-repudiation of sender ensures that someone sending a message should not be able to deny later that he or she sent it. Non-repudiation of receiver means that the receiver of a message should not be able to deny that she received it. Cryptography can be used to provide non-repudiation by providing unforgeable messages or replies to messages.

Non-repudiation is useful for financial, e-commerce, and contractual exchanges. Non-repudiation is accomplished by having the sender and/or recipient to digitally sign some unique transactional record.

Attestation

Attestation is the act of "bearing witness" or certifying something for a particular use or purpose. (For example, Digital Rights Management is interested in attesting that your device or system hasn't been compromised with some back-door to allow someone to illegally copy DRM-protected content.) Cryptography can be used to provide a "chain of evidence" that everything is as it is expected to be to prove to challenger that everything is in accordance with the challenger's expectations. For example, remote attestation can be used to prove to a challenger that you are indeed running the software that you claim that you are running. Most often, attestation is done by providing a chain of digital signatures starting with a trusted (digitally signed) boot loader. An example of this is the secure boot loader that comes with Microsoft Windows 8 on computers supporting Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI).

This OWASP Development Guide will not discuss the use of cryptography for attestation purposes further as it is not something with which most developers will have to deal. Attestation is generally discussed in the context of a Trusted Platform Module (TPM), Digital Rights Management (DRM), and UEFI Secure Boot.

Cryptographic Primitives

Cryptographic Hashes

Cryptographic hashes, also known as message digests, are functions that map arbitrary length bit strings to some fixed length bit string (referred to as the "hash value" or "digest value"). These hash functions are many-to-one mappings that are compression functions. To be useful in a cryptographic sense, a hash function H operating on input x such that digest value d = H(x), hash function H must have the following three properties:

They must be one-way functions. That is, given hash algorithm H and digest value d, it is computationally infeasible to compute input x.

Given input x such that d = H(x), it is computationally infeasible to find a second input x', such that H(x') yields the same digest value d.

It is computationally infeasible to find two different inputs, x and x' such that both hash to the same value; that is, such that H(x) == H(x') where x != x'. Such cryptographic hash functions are used to provide data integrity (i.e., to detect intentional data tampering), to store passwords or pass phrases, and to provide digital signatures in a more efficient manner than using asymmetric ciphers. Cryptographic hash functions are also used to extend a relatively small bit of entropy so that secure random number generators can be constructed.

When used to provide data integrity, cryptographic functions come in two flavors, keyed hashes (called "message authentication codes") and unkeyed hashes (called "message integrity codes"). Hash algorithms to avoid: MD2, MD4, MD5, SHA-0 (aka, SHA), and any hash algorithm based on Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC).

- Hash algorithms to avoid (except as required by legacy code): SHA-1

- Recommended hash algorithms: SHA-2 (i.e., SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, and SHA-512), SHA-3 (aka, Kecak)

Ciphers

A cipher is an algorithm that performs encryption or decryption. Modern ciphers can be categorized in a couple of different ways. The most common distinctions between them are:

- Whether they work on fixed size number of bits (block ciphers) or on a continuous stream of bits (stream ciphers).

- Whether the same key is used for both encryption and decryption (symmetric ciphers) or separate keys for encryption and decryption (asymmetric ciphers).

Symmetric Ciphers

Symmetric ciphers encrypt and decrypt using the same key. This implies that if one party encrypts data that a second party must decrypt, those two parties must share a common key. Symmetric ciphers come in two main types:

- Block ciphers, which operate on a block of characters (typically 8 or 16 octets) at a time. An example of a block cipher is AES.

- Stream ciphers, which operate on a single bit (or occasionally a single byte) at a time. Examples of a stream ciphers are RC4 (aka, ARC4) and Salsa20. Note that all block ciphers can also operating in "streaming mode" by selecting the appropriate cipher mode.

Recommendations

- Symmetric cipher algorithms to avoid: DES, using any algorithm with a key size of less than 80 bits

- Symmetric cipher algorithms to avoid (except as required by legacy code): RC4 (Note: RC4 is very badly broken. It should be considered for replacement even for legacy use.) Recommended symmetric cipher algorithms: AES, 3-key Triple DES (aka, DESede[2]), Salsa20

Cipher Modes

Block ciphers can function in different modes of operations known as "cipher modes". This cipher mode algorithmically describes how a cipher operates to repeatedly apply its encryption or decryption mechanism to a given cipher block. Cipher modes are important to have an awareness of because they have an enormous impact on both the confidentiality and the message authenticity of the resulting ciphertext messages.

The simplest cipher mode---and unfortunately often the only one introduced in introductory textbooks or cryptography examples---is known as Electronic Codebook (ECB). ECB mode is simply a repeated application of the block cipher's raw encryption (or decryption) operation on the corresponding block of plaintext (or ciphertext for decryption). As simple as ECB mode is, it almost always should be avoided as it is fraught with various easily exploitable cryptographic vulnerabilities. All cipher modes other than ECB require an "initialization vector" (IV) to initialize the encryption process.

Almost all cryptographic libraries support the four original DES cipher modes of ECB, CBC (Cipher Block Chaining), OFB (Output Feedback), and CFB (Cipher Feedback). Many also support CTR (Counter) mode.

The discussion of all the nuances of cipher modes is beyond the scope of this document; however, some further comments will be discussed about cipher modes a bit later. [3]

Initialization Vectors

In cryptography, an initialization vector (IV) is a fixed size input to a block cipher's encryption / decryption primitive. The IV is recommended (and in many cases, required) to be random or at least pseudo-random. We will discuss IVs and their related requirements later in this document.

Padding

Block ciphers generally operate on fixed size blocks (the exception is when they are operating in a "streaming" mode). However, these ciphers must also operate on messages of any sizes, not just those that are an integral multiple of the cipher's block size.

Asymmetric Ciphers

Asymmetric ciphers encrypt and decrypt with two different keys. One key generally is designated as the private key and the other is designated as the public key. The public key generally is widely shared.

Asymmetric ciphers are several orders of magnitude slower than symmetric ciphers. Because of that, they are used frequently in hybrid cryptosystems, which combine asymmetric and symmetric ciphers. In such hybrid cryptosystems, a random symmetric "session" key (i.e., a key only used for the duration of the encrypted communication) is generated. This random session key is then encrypted using an asymmetric cipher and the recipient's private key. The plaintext data itself is encrypted with the session key. Then the entire bundle (encrypted session key and encrypted message) is all sent together. Both TLS and S/MIME are common cryptosystems using hybrid cryptography.

Practices to avoid

With all asymmetric ciphers, chosen plaintext attacks [4] are always a concern. Because the public key is always considered as known to potential adversaries, attackers can always encrypt any arbitrary plaintext and observe the resulting ciphertext. Ordinarily, this is not a cause for concern because the plaintext that is to be encrypted with an asymmetric cipher is highly unpredictable (e.g., encrypting session keys or cryptographic hash values). However, chosen plaintext attacks become an issue when using public-key crypto to encrypt highly structured / regular plaintext, especially when that plaintext has a limited length to make encrypting of all possible plaintexts practical. Consider the ill-advised scenario where an application is using RSA encryption to encrypt plaintext social security numbers or bank account numbers and then storing the resulting ciphertext into the application's database. An inside attacker who as access to the database (but not the RSA private key) could use the RSA public key (which we assume is available) and use it to encrypt all possible SSNs, keeping a map of SSN to ciphertext. The attacker could then use the resulting ciphertexts to determine which plaintext SSN corresponds to which DB record by searching by the ciphertext SSN in the database. Consequently, asymmetric encryption algorithms should generally be avoided when the plaintext follows some predictable format or it can largely be enumerated over all possible plaintext values. For such situations, one should use symmetric ciphers instead.

Cipher Modes and Padding for Asymmetric Ciphers

Cipher modes and padding are still pertinent to asymmetric ciphers, however the cipher mode is almost always ECB [5]. (This is not a problem when the data being encrypted is a random session key.) For padding, generally some form of OAEP is used. PKCS5 (or PKCS7) padding should generally be avoided with asymmetric encryption.

Note that encryption using asymmetric ciphers and OAEP has some limitation though. For example, when OAEP is used as a padding scheme for RSA (that is, RSAEP-OAEP is being used), PKCS1 v2 states that the maximum length of any message that may be encrypted using RSA is:

k - (2 * hLen) - 2

where k is the RSA modulus length

and hLen is the # of octets in the chosen hash function.

- Asymmetric cipher algorithms to avoid: TBD

- Asymmetric cipher algorithms to avoid (except as required by legacy code): TBD

- Recommended asymmetric cipher algorithms: RSA with at modulus of at least 2048-bits, Elliptic Curve (see Daniel J. Bernstein's and Tanja Lange's http://safecurves.cr.yp.to/index.html and/or NIST FIPS 186-3 for recommended curves)

Digital Signatures

Digital signatures are a cryptographically unique data string that is used to ensure data integrity and prove the authenticity of some digital message. and that associates some input message with an originating entity. A digital signature generation algorithm is a cryptographically strong algorithm that is used to generate a digital signature.

Key Exchange and Key Agreement Algorithms

Key exchange algorithms (also referred to as key establishment algorithms) are protocols that are used to exchange secret cryptographic keys between a sender and receiver in a manner that meets certain security constraints. Key exchange algorithms attempt to address the problem of securely sharing a common secret key with two parties over an insecure communication channel in a manner that no other party can gain access to a copy of the secret key. Traditionally this has relied on two humans somehow securely exchanging keys out-of-band; e.g., via a direct face-to-face meeting or mailing an attachment as an encrypted zip file that is encrypted with a previously shared passphrase, etc. However, the traditional methods do not allow two unknown parties who have never met to exchange a secret key with each other. In fact, proof of (or at least, high confidence in) identity is a major unsaved problem in such cases.

Key agreement protocols are protocols whereby N parties (usually two) can agree on a common key without actually exchanging the key. When designed and implemented properly, key agreement protocols are preventing adversaries from learning the key or forcing their own key choice on the participating parties.

This Development Guide will discuss key exchange and key agreement algorithms later in the context of key management.

Common Cryptographic Concerns

Too often, cryptography is treated as a silver bullet for security, but many times it is poorly implemented or simply misapplied, causing at best no additional security and at worst, weakened security.

Therefore, knowing how to apply cryptography correctly is just as important as knowing when to apply it. All too often a sufficient key length and a strong cipher (e.g., using AES with a 256-bit key) is used incorrectly in ways that can significantly weaken it or even make it useless.

Providing Confidentiality

Using cryptography for encryption to prevent disclosure of data is one of its most common uses, but one needs to be careful in how one uses cryptography to encrypt. There is more to it than simply picking a strong algorithm and a sufficiently large key size; getting it wrong means you only have provided the illusion of security.

Choosing a Cipher Type: Streaming vs. Block Ciphers

The first choice when encrypting is to decide whether a block cipher or a stream cipher (or equivalently, a block cipher operating in streaming mode) is the most appropriate. If the output is coming in as a continuous stream and you are simply forwarding on as an encrypted stream, then use a stream cipher or a cipher operating in streaming mode. If the input is chunked (e.g., reading blocks from a file) or you want to encrypt something and store the ciphertext for some period, then you probably should use a block cipher.

Choosing a Cipher Specification: Algorithm, Cipher Mode, Padding, and Key Size

Choosing an Algorithm

If you chose a block cipher, AES is your best choice. Don't use anything else unless you need it to support legacy systems or you need an algorithm that is intentionally slow (e.g., when computing password hashes; consider how bcrypt uses Blowfish because of its slow key setup).

If you really must select a stream cipher, Salsa20 is a good choice, but using a streaming cipher mode with a block cipher such as AES will work just as well and is the recommended way to go, as that approach has options that are more flexible, especially since Salsa20 is not widely implemented outside of C, C++, and Python. RC4 is acceptable for legacy software where it is required for compatibility, but in general, you should avoid it because of known cryptographic weaknesses.

Authenticated vs. Non-authenticated Encryption

Authenticated Encryption (AE) is any block cipher mode that provides confidentiality, data integrity, and authenticity of the data. Specifically, AE ensures the authenticity of the ciphertext (or more generally, the IV and ciphertext) in a manner that can guarantee that the IV and/or ciphertext has not been tampered with. This is important as it prevents chosen ciphertext attacks such as padding oracle attacks.

In general, one should prefer authenticated encryption modes whenever there is a chance that an adversary may have a chance to alter or provide the IV and/or ciphertext that you are attempting to decrypt. (A good reason to develop a threat model before you design your encryption.)

Recommended AE cipher modes are Counter with CBC-MAC (CCM) and Galois/Counter Mode (GCM). Both CCM and GCM are NIST approved and patents encumber neither. CCM is the simpler of the two and thus less likely to be fraught with side channels in its implementations. GCM is supposedly more parallelizable so may provide better throughput (at least when implemented in hardware), but it seems to make many cryptographers nervous because there are so many things to get exactly right. [Note to Java developers: Oracle's JDK 7 now supports both CCM and GCM in the SunJCE. If you are using an earlier JDK release, you can use Bouncy Castle as your JCE provider. In lieu of using an AE cipher mode, you can "wrap" an HMAC around the IV and ciphertext and check its validity before decrypting. (The so-called "encrypt-then-MAC" approach. [6]) This is the approach that OWASP ESAPI 2.x (Java) has taken when an AE cipher mode is not available; in fact, it is ESAPI 2.x's default mode for symmetric encryption. There is no standard supported AE mode in Microsoft's .NET Framework, however some members of the .NET security team have made a .NET assembly supporting both CCM and GCM modes available here. A more complete list of authenticated encryption modes may be found on the NIST Modes Development page. Note that if no AE mode is available and you decide to use the encrypt-then-MAC approach, do not use the same key for both the encryption and the MAC.

Cipher Padding

A streaming cipher or a block cipher using a streaming mode such as OFB, CFB, CTR, etc. does not require padding. However, we recommend that you use padding with any block cipher that uses a block mode (e.g., CBC). For symmetric block ciphers, PKCS7 (RFC 5652) or PKCS5 padding are good choices as they are supported by almost all cryptographic libraries. For most practical purposes, PKCS5 padding is the same as PKCS7 padding, except that technically, PKCS5 padding can only be used to pad ciphers whose block size is 64 bits (In fact, the standard SunJCE cryptographic provider in Java supports only PKCS5 padding, but not PKCS7 padding. On the other hand, the .NET Framework supports only PKCS7 padding, but not PKCS5 padding. Fortunately, in practice, these two padding schemes can generally be used interchangeably.) For asymmetric ciphers, one needs to be more cautious in the choice of padding because of cryptographic weaknesses with some padding schemes used with such ciphers. For the RSA algorithm, we recommend the OAEP padding scheme OAEP with SHA-1 and MGF1 padding (OAEPWithSHA1andMGF1Padding)

Recommended: Block ciphers using block mode – PKCS7 or PKCS5 padding; with RSA - OAEPWithSHA1andMGF1Padding

A Final Word About Cipher Modes

Using a cipher in its "raw" form is referred to as Electronic Code Book (ECB) mode. When encrypting using ECB, the plaintext message is divided into blocks (corresponding to the cipher algorithm's block size) and each block is encrypted individually with no interaction with any other blocks. Unfortunately, except when the plaintext message is less than the cipher's block size (typically 128 or 64 bits) or one is encrypting completely random data (e.g., using a asymmetric cipher to encrypt a key for a symmetric cipher). ECB mode should generally be avoided in all other cases because it has many cryptographic weaknesses. Normally, an AE cipher mode (see "Authenticated vs. Non-authenticated Encryption", above) should be used. However, all cipher modes other than ECB require an "initialization vector" (IV). An IV usually is a random or pseudorandom bit stream that has the same length as the cipher block size. In any streaming cipher mode, it is important that for any given encryption key, the same IV never be used to encrypt multiple plaintext messages.

Therefore, either ensure you use a different IV or a different key whenever you use a stream cipher or a symmetric cipher in a streaming mode. Since it is generally easier to change the IV instead of the key (since the latter needs to be securely transmitted with the intended recipient of the ciphertext), it is recommended that you construct the IV in such cases by breaking it into two parts: one part being a time stamp in at least millisecond resolution and the other a counter. Figuring out how many bits to dedicate for the counter depends on what you think the maximum number of messages you can encrypt in a clock increment (millisecond, nanosecond, or whatever resolution you are using) combined with how long you will encrypt for with the same encryption key. With IVs that are 128-bits in length, you should have plenty of room for both. In general, it is highly recommended that you change the encryption key at least once a year. (PCI DSS requires at least this; but generally, more frequently is recommended.) Because of the way stream ciphers work (or block ciphers operating in a streaming cipher mode), if you do use the same encryption key / IV pair to encrypt multiple plaintext messages, an adversary can simply take the resulting ciphertext streams and XOR them together. The result of this operation leaves a bit stream of the two plaintext messages XOR'd together, which the adversary can then analyze using statistical frequency analyzing leading to the discovery of the two original plaintext messages. [7]

Okay, okay, so that was more than a final word. How about this for a summary:

It's hard to go wrong with a properly implemented crypto system built with AES with CBC mode using PKCS#7 padding and random IVs that uses an HMAC-SHA256 to provide an encrypt-then-MAC approach.

If that sounds like an advertisement for ESAPI 2.x, it's not. It's just the advice that ESAPI symmetric encryption followed.

Ensuring Data Integrity

Another use of cryptography is to detect intentional (or unintentional, for that matter) tampering of data--that is, to ensure data integrity. There are three general approaches to this, depending on the exact needs.

To ensure the integrity of data during file downloads where you exclusively control the data, using a Message Integrity Code (MIC), generally implemented via a secure one-way cryptographic hash, is sufficient. A MIC is simply an unkeyed hash. In such cases, you would have links from which to download the file along with the MIC hash code listed. (The expectation being, that once someone downloads the file, they calculate the cryptographic hash themselves---usually using SHA1 or MD5---and che#ck it against what is listed on your website.

On the other hand, if you expect your downloads to be mirrored to other sites which you do not control---that is, to potentially untrusted sites---then using a MIC (unkeyed hash) is not sufficient because an adversary could tamper with your data and then simply recalculate the hash on the tampered data and publish the new hash for the file. They could do that, simply because calculating the hash does not require the adversary knows any secrets. In such cases, you will want to digitally sign the bytes of the file with your private key and publish your public key on your website. Typically, a utility like Gnu Privacy Guard (gpg), although often the installer software such as rpm or apt-get will do this for you as part of the download / installation process. (Further details of how to use these utilities are beyond the scope of this document. See the relevant manual pages for details.)

Digital signatures of course are also useful for signing other things, for instance dynamically created documents. Another mechanism of "signing" data is via a Message Authentication Code (MAC), which is just a signed cryptographic hash. While both digital signatures and MACs are used to "sign" data to ensure its integrity, each have their specific use. Because digital signatures use public / private keys, they are appropriate when 1) an identity should be associated the data or 2) when the data's integrity needs to be verified by a large group. Because a MAC uses a shared secret key, it does not scale well when a large number of entities need to verify the same data. However, MACs have an advantage of speed so they are often used in cases where a secret key has already been established and shared between two entities such as when providing message authenticity (i.e., ensuring data integrity) to encrypted messages. For example, a MAC is used with encryption in the previously discussed "encrypt-then-MAC" approach. In that approach, the usually approach is to take a secret key and to use it to derive two separate keys, one used for encrypting with a symmetric cipher and the other used for the key to the MAC algorithm. A "key derivation function" is used to securely derive two keys from a single key.

Recommendations for algorithms:

For MIC: Because of the assumption that you are the only one that controls the bits and the hash signature, any secure one-way hash will do. SHA1 or MD5 are generally adequate because in this case the algorithms are really only acting as a checksum, much as a 32-bit CRC might be used. However, if there is concern that an adversary can attempt collisions but for some reason not change the hash signature (e.g., maybe it's built into some widely distributed software), then use a stronger hash algorithm such as SHA-256.

For MAC: HMAC-SHA1 is acceptable. HMAC-SHA256 or HMAC-SHA3 (aka, Keccak) is recommended for new applications and/or long term use.

For Digital Signatures: RSA. DSA may be used in a pinch but is should be avoided because it is much more sensitive to implementation flaws.

Cryptography for Authentication

We use cryptography for authentication in two different ways. First, cryptographic protocols are used to securely authenticate entities over an insecure communication channel. Some of these more widely known communication protocols include Kerberos, RADIUS, and MS-CHAPv2. If, as a developer, you have need of authentication protocol, you are advised to either use a standard one known to be secure or work with a reputable professional cryptographer to develop one to suit your needs. History is replete with examples from broken authentication protocols even when they are developed by experts. A prime example is the original Needham-Schroeder protocol. Hire a professional cryptographer as this use of cryptography is much harder than it seems.

The second way that cryptography is used for authentication is for storing a user's password. Unless the user's password must later be replayed in a separate context to make the plaintext password available to some other downstream system (possibly when the user is no longer even authenticated to the present system), the recommended way to do this is to use a strong, one-way secure cryptographic hash along with "salting" (adding a nonce of sufficient length).

Using Cryptography to Solve Practical Problems

Among the two most common uses of cryptography securing data-at-rest (e.g., stored in a file or a database) and securing data in transit. When we use the term "securing" data via cryptography, we are generally referring to providing confidentiality and ensuring data integrity / authenticity. That is the minimum expectations of using cryptography to "secure" data as discussed in this section and subsections.

Securing Data at Rest

Introduction

When it comes to stored data-at-rest so that it is encrypted in an SQL database, there are three commonly practiced approaches:

- The SQL database engine itself handles the encryption and decryption. Examples of this are Oracle Database "Transparent Data Encryption" and Microsoft SQL Server "Transparent Data Encryption". (We will refer to these as Oracle TDE and SQL Server TDE respectively, and just refer to the technology as TDE in general.)

- The application code completely handles the encryption and decryption of the sensitive data before it is stored in and after it is retrieved from said database, as well as ensuring its authenticity.

- An appropriate proxy (for example, MIT's CryptDB or a custom web service that clients start using to access the data rather than accessing it directly) between the application and the database handles all the encryption / decryption.

Each of these approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages of securing data-at-rest stored in a database. Exploring all of these pros and cons is beyond the current scope of this wiki page, although this may be provided in the future should the need warrant. The present purpose of this document is to provide some background for understanding why the pros and cons of each approach and to understand the threat models that each of these approaches address.

General Approaches

Database Engine Transparent Data Encryption (TDE)

How It Works (General Description)

In this technology, the DB engine itself (e.g., Oracle Database, Microsoft SQL Server Database) handle the encryption and decryption and usually can be configured to handle the key management issues as well.

TDE usually offers encryption at the column, table, and tablespace levels. TDE only supports limited encryption algorithms (most typically, AES and 3DES) and assorted key lengths. There usually are (at least) 2 keys involved. One, is the DB "master" key. This master key is usually secured with a pass phrase / password which ideally is controlled by an application team who is considered the data custodian for the to-be-encrypted data. This master key is then used to derive other specific DB key encryption keys that encrypt specific columns, tables, or tablespaces.

Most often, the DB engine uses the CBC cipher mode and something like PKCS7 padding (which Java refers to as PKCS5Padding) to handle the encryption. Also, with TDE, there are usually two modes of operation...deterministic encryption and non-deterministic encryption. This translates into whether or not each individual item being encrypted (generally, a record, when encrypting a column) uses unique Initialization Vector (IV) [sometimes referred to as 'salt' by the DB vendors] or not. Deterministic encryption uses the same IV for all records; non-deterministic encryption uses a unique IV for each record that is encryption and this IV is maintained in a manner that is transparent to the DB access. Deterministic and non-deterministic encryption will be discussed later in more detail in the Advantages and Disadvantages subsection to follow.

Key management normally consists of distributing a file containing the password-encrypted DB master key along with making the password or passphrase known to whomever needs to decrypt this master key in order to provide it to the database engine. If this master key file and password are placed within the database itself (which is the easiest to implement), then the database engine will automatically decrypt its encrypted data. However, this scenario does not protect the sensitive encrypted data from a rogue DBA or system administrator (see the "General Threat Model" subsection, below), so frequently it is recommended that the application team or some other independent data custodian becomes responsible for managing this password-encrypted master key. (Note: Some TDE implementations use a separate private key contained in a keystore file to decrypt the master secret key, but the ideas as the same. In such cases, this private key ideally should be password protected when stored in the keystore file.) Further discussion of key management for SQL Encryption purposes is beyond the scope of this document.

General Threat Model

Like encryption used for any purpose--be it authentication, confidentiality, data integrity, etc.--one needs to ask "what is your threat model?". In other words, what particular threat agents are you trying to prevent which particular assets via what particular attack vectors? For the case of TDE, the vendors generally do not explicitly document a threat model. Instead, they vaguely hand wave and point to something like section 3.4 of the PCI Data Security Standard and state "we satisfy those requirements". However, when one looks closely at these PCI DSS requirements as well as the vendor-specific TDE behavior, it usually becomes clear that the general threat model these vendors have in mind is someone like a rogue DBA or other rogue operations person doing a "smash and grab" of a hard drive where the encrypted database resides or attempting to steal confidential encrypted data from some offline backup of the database.

From the perspective of a security engineer, that is a very narrow threat model is it does nothing to reduce attacks to an online encrypted database (which presumably is the usual, or at least preferred, state of one's DB). And indeed, this particular niche attack vector can only be effectively mitigated if one does proper key management as alluded to above. If the file (or as Oracle prefers to call it, the "wallet") containing the password-encrypted DB master key is made available to the DBA, this mitigation is no longer available. (In terms of Oracle TDE, we would restate this if is arranged that the Oracle wallet is auto-opened when the database comes up, then the encryption that Oracle TDE provides you does not even sufficiently protect you against this particular niche attack vector.)

Advantages

Given that the threat model for DB Engine TDE is so narrow, why use a TDE solution at all? Indeed, that is the $64,000 question.

In a nutshell, it's because the solution is cheap. It is almost 100% transparent (at least when using deterministic encryption) to the applications accessing the encrypted data stored in the database and because of that, it is a very inexpensive solution to deploy. When one adds to that the fact that it can satisfy the letter of the law of regulatory policies (such as section 3.4.x of PCI DSSv2), often that's all that it takes. Such companies often take a security-by-checklist approach because they are more concerned with fines failing to meet regulatory compliance issues than they are in reduce losses from potential security breaches.

At other times, while it is recommended as a very poor solution, it may be the only feasible solution, especially for legacy databases. For example, if your company has 20 or so applications accessing some database where very sensitive data such as (say) full-credit card numbers are stored and those applications are a combination of third-party applications, Cobol applications, C/C++ applications, Java applications, and .NET applications, it is often very difficult or prohibitively expensive to design a common, secure solution that will work for all 20+ applications. (The "Encryption By Proxy" approach can approach this, but it has some significant performance issues and still is not ready for production-deployment.) And when faced with impending large fines from PCI or other regulatory bodies for not being in compliance for securing data-at-rest, the TDE approach starts looking like the ideal candidate to those in upper management.

Disadvantages

The disadvantages of the DB Engine TDE approach are great. The major ones are:

- Because the DB engine itself decrypts all the data transparently to clients, once the DB is provided the decrypted master key, any client having query access to the encrypted columns will have access to the decrypted data. If this is not the desired state, in order to keep the data secure, the database access model often needs to be significantly revamped to construct separate DB views for each different use case actor with legitimate access to at least portions of the database.

- Deterministic encryption is usually the preferred solution by both database administrators and application developers, but unfortunately it has numerous short-comings. With deterministic encryption, the same plaintext will always encrypt to the same ciphertext (at least until a key change operation is done to generate new DB key encryption keys). However, for the same reasons that we do generally require unique IVs (even for CBC mode; in any other mode, it is a major disaster in the making), deterministic encryption is not considered secure. The details of these cryptographic attacks are beyond the scope of this document. However, using non-deterministic encryption with a unique IV (or "salt") per record results in stronger encryption but does not allow the DB engine to do indexed searching on that specific column. For cases where the sensitive plaintext data is something where all possible plaintext values are easily enumerated (for example, with Social Security Numbers), this allows someone who would have access to the ciphertext stored in the database who also has insert or update access to create records with all possibilities. Those ciphertext values can then be compared to the other identical ciphertext values in the database and that can be used to determine the plaintext by the attacker simply keeping a mapping of plaintext to ciphertext. This is an attack that could be done by a rogue DBA even though that DBA does not know the DB TDE encryption key. Had non-deterministic encryption been chosen instead, such a simple enumeration attack would not be possible.

- When backup copies of an open / online database are made, certain types of these backups make copies of the decrypted data so that anyone having access to the backup copies has access to the sensitive plaintext data that had been encrypted. Examples for Oracle include backups made via the "Data Pump export utility (expdp)" or "explicit captures" made via Oracle streams. (See the section "Using Data Pump with TDE" for the former and "How Oracle Streams Works with Other Database Components" for details of the latter.) Similar issues are expected with Microsoft SQL Server backups but have not been verified. Therefore, this may require changes to the database backup procedures.

- Because the sensitive data sent to the database is plaintext, passive network sniffing attacks are a major concern. Consequently, the database connection should be established over TLS, IPSec, or some other secure communication channel.

Application Level Encryption

How It Works (General Description)

Application level encryption refers to encryption that is considered part of the application itself; it implies nothing about where in the application code the encryption is actually done. In a typical 3-tier web application, the encryption most often is done in the application server before being sent to the database. Thus--in this design--the database is only sent ciphertext, not the sensitive plaintext (compare that to the TDE case, above).

An alternate approach is to do all the encryption / decryption as stored SQL procedures, possibly invoked via DB triggers. This design is very similar to the DB TDE approach discussed above with the biggest difference is that it has all the disadvantages and none of the advantages (such as minimal development costs). Because of this, for the rest of this section we assume encryption / decryption is handled in the application server and not done within the DB via stored procedures.

General Threat Model

It goes without saying (but we will say it otherwise), that for this approach the application developers are trusted in some sense. While they may not (and indeed, should not) be trusted with the encryption keys, the must be trusted to produce secure code to handle the encryption. (Contrast this to the implied threat model for TDE where the DB vendor is trusted to produce secure code and DBAs are considered trusted. While application developers also trusted not to leak sensitive information--either intentionally or unintentionally--they do not have to be trusted with writing the encryption code in the case of TDE.)

Advantages

- Like the TDE approach, a smash and grab of an offline copy of the database will contain only ciphertext. Unlike the TDE approach, the same is true of a direct DB dump of an online database. Given that the ideal state of one's production database is that it is online, this is an important distinction.

- An advantage of handling the encryption outside of the database is that--if done correctly--one need not be overly concerned about the contents of the database being stolen. In the face of SQL injections where an external attacker can sometimes dump database table contents remotely, this can be an important advantage. Compare this to the TDE solution, where the database would transparently decrypt the data when a SQL injection occurs. This does not mean that this is approach is completely immune to data leakage via SQL injection attacks, but it does lower the likelihood.

- Because the application controls the entire encryption / decryption process, one can also provide for data integrity across the entire record. This can be used to prev

Disadvantages

- In terms of initial layout and ongoing software support costs, this is likely to be the most costly of the three solutions.

- The application developers need to understand cryptography w

- ell enough to develop secure cryptographic solutions. Given that this is a relatively rare skill for application developers, its importance should not be overlooked.

- In addition to the actual encryption / decryption solution, the application must also handle the ancillary functions of secure key management which is anything but trivial. This includes, but is not limited to key distribution and key change operations.

Encryption By Proxy

TODO - mention CryptDB here, and any others.

How It Works (General Description)

TODO

General Threat Model

TODO

Advantages

TODO

Disadvantages

TODO - These sections to be covered later, should the need arise. Performance is a likely issue.

Securing Data in Transit

TODO

Key Management

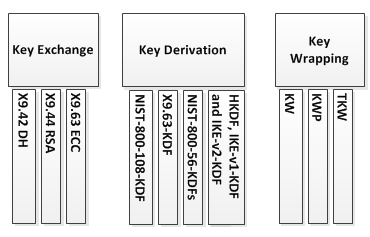

The following diagram shows standards relevant to key management:

Oasis Cryptographic Key Management provides a comprehensive list of bodies and standards for Key Management inclduding NIST SP 800-130 A Framework for DesigningCryptographic Key ManagementSystems

For the Financial Services industry the main standards and references are

- ANSI X9.24 Retail Financial Services Symmetric Key Management Part 1: Using Symmetric Techniques for the Distribution of Symmetric Keys

- ANSI X9 X9.24-2-2006 Retail Financial Services Symmetric Key Management Part 2: Using Asymmetric Techniques for the Distribution of Symmetric Keys

- PCI PIN Security Requirements v2

Key Derivation

A key derivation function (KDF) is a deterministic algorithm to derive a key of a given size from some secret value. If two parties use the same shared secret value and the same KDF, they should always derive exactly the same key.

PBKDFs (Password Based Key Derivation Functions) are designed to encrypt data, typically keys, based on a password. The password is mixed with a salt (e.g. random 8 bytes) to form an intermediate key (Key Encryption Key) and this is used to encrypt the data/key.

Passwords have a relatively small keyspace (limited by typeable characters on a keyboard and passwords that people can remember) compared to randomly generated data of the same length.Therefore, a salt is added to prevent dictionary attacks. The process is repeated many times (based on a count e.g. 1000) to deter brute force attacks (key stretching).

NIST SP 800-108 Recommendation for Key Derivation Using Pseudorandom Functionsand NIST 800-56C Recommendation for Key Derivation through Extraction-then-Expansion are NIST approved KDFs.

SP 800-135 Rev 1 Recommendation for Existing Application-Specific Key Derivation Functions lists security requirements for other KDFs e.g. HKDF, IKE-v1-KDF and IKE-v2-KDF, X9.63-KDF.

Key Wrapping

Key wrapping is a construction used with symmetric ciphers to protect cryptographic key material by encrypting it in a special manner. Key wrap algorithms are intended to protect keys while held in untrusted storage or while transmitting keys over insecure communications networks. NIST has defined a special AES key wrap specification which is supported in the Java Cryptography Extensions that is performed using Cipher.WRAP_MODE and Cipher.UNWRAP_MODE as the operation mode to Cipher.init(). (Althernately, in newer versions of the JDK, you can just call Cipher.wrap() and Cipher.unwrap() respectively.)

Key Exchange

Key exchange algorithms (also referred to as key establishment algorithms) are protocols that are used to exchange secret cryptographic keys between a sender and receiver in a manner that meets certain security constraints. Key exchange algorithms attempt to address the problem of securely sharing a common secret key with two parties over an insecure communication channel in a manner that no other party can gain access to a copy of the secret key. Traditionally this has relied on two humans somehow securely exchanging keys out-of-band; e.g., via a direct face-to-face meeting or mailing an attachment as an encrypted zip file that is encrypted with a previously shared passphrase, etc. However, the traditional methods do not allow two unknown parties who have never met to exchange a secret key with each other. In fact, proof of (or at least, high confidence in) identity is a major unsolved problem in such cases.

Key Agreement protocols are protocols whereby N parties (usually two) can agree on a common key with all parties contribute to the key value. When designed and implemented properly, key agreement protocols prevent adversaries from learning the key or forcing their own key choice on the participating parties.

The most familiar key exchange algorithm is Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange. There are also password authenticated key exchange algorithms. RSA key exchange using PKI or webs-of-trust or trusted key servers are also commonly used.

Key Transport protocols are where one party generates the key and sends it securely to the recipient(s).

The selection of schemes specified in NIST Special Publication 800-56ARevision 2Recommendation for Pair-Wise Key Establishment Schemes Using Discrete Logarithm Cryptographybased on standards for key-establishment

Key Exchange protocols based on different primitives are available:

- X9.42 Public Key Cryptography for the Financial Services Industry: Agreement of Symmetric Keys Using Discrete Logarithm Cryptography:

- This standard, partially adapted from ISO 11770-3 (see [13]), specifies schemes for the agreement of symmetric keys using Diffie-Hellman and MQV algorithms. It covers methods of domain parameter generation, domain parameter validation, key pair generation, public key validation, shared secret value calculation, key derivation, and test message authentication code computation for discrete logarithm problem based key agreement schemes

- X9.44 Key Establishment Using Integer Factorization Cryptography.

- Key transport based on the RSA algorithm.

- X9.63 Public Key Cryptography for the Financial Services Industry: Key Agreement and Key Transport Using Elliptic Curve Cryptography

Key Transport protocols used in the financial industry:

- ASC X9 TR-31-2005 - Interoperable Secure Key Exchange Key Block Specification for Symmetric Algorithms specified a scheme for transporting a key based on a pre-existing shared key.

- ASC X9 TR-34 Interoperable Method for Distribution of Symmetric Keys using Asymmetric Techniques: Part 1 - Using Factoring-Based Public Key Cryptography Unilateral Key Transport is similar to X9 TR-31 but uses asymmetric ciphers (to avoid having to have a pre-existing symmetric key). It uses CMS EnvelopedData (X9.44 OAEP), and SignedData types (X9.44 RSASSA-PKCS-v1_5).

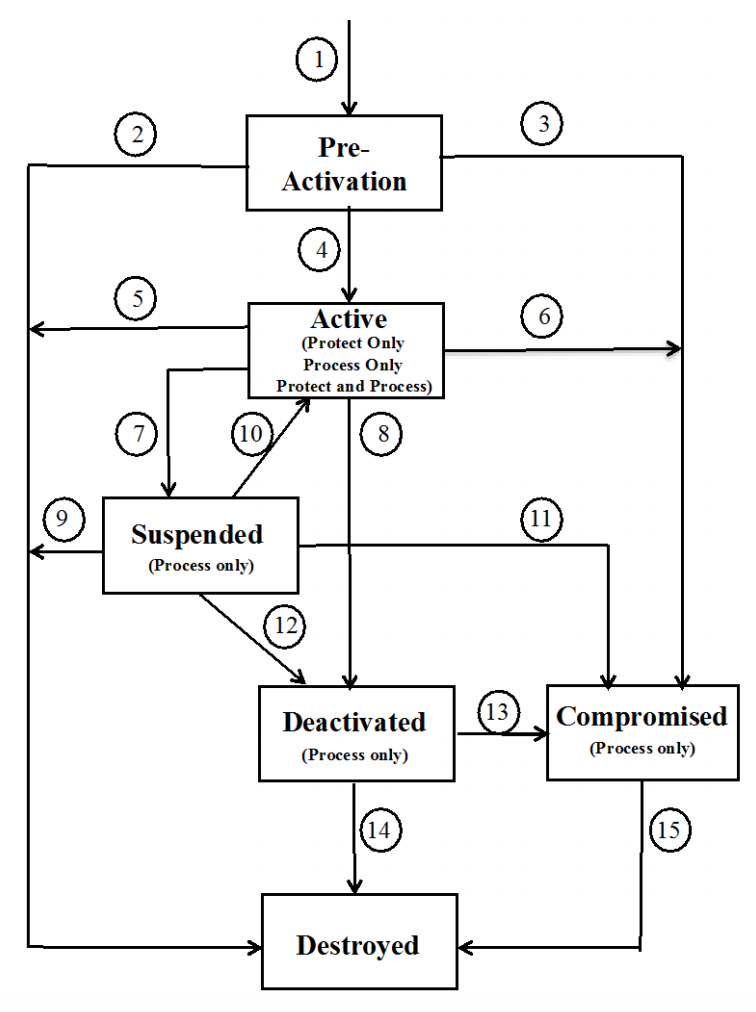

Key Lifecycle

The following "Key States and Transitions" diagram is from page 76 of http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-57pt1r4.pdf It is relevant to the following discussion.

Generation

Keys start out in the "pre-activation" state.

NIST SP 800-133 Recommendation for Cryptographic Key Generation discusses the generation of keys to be used with the approved cryptographic algorithms.

ANSI X9.24 Part 1 provides details on what forms keys can exist outside the Secure Cryptographic Device (SCD) e.g. Hardware Security Module (HSM) that they were generated in.

Symmetric Keys

For symmetric keys (e.g. AES, DES), the highest level key is generated randomly e.g. 16 bytes from an RNG for an AES-128 key.

If there is no prior trust with the receiving entity then the highest level symmetric key is generally split into multiple plaintext components for distribution to the other party via out-of-band manual means.

Key operations that involve people generally require at least dual control split knowledge to ensure no one person has all the key material e.g. 2 parties have a key or password component that is only effective when combined with the other part.

Further keys may be derived from this highest level key e.g. using a KDF with device identifier or serial number as input.

In general a tag-and-bag scheme is used for these keys:

- tag: since the key is just random bytes the end user needs to know information about the key when they receive it e.g. what the key should be used for, the algorithm to use e.g. DES or AES , etc... This information is represented by additional information that is distributed with the key and is called a Key Block Header (KBH)

- bag: cryptographic schemes are applied to the key such that Confidentiality-Integrity-Authenticity is assured.

Examples include:

- ANSI X9 TR-31 2010 Interoperable Secure Key Exchange Key Block Specification for Symmetric Algorithm

- Key Management Interoperability Protocol Specification Version 1.1

- CMS NamedKeyEncryptedData type (with additional authentication added via MAC or signature)

Asymmetric Keys

Asymmetric keys are generated based on the mathematical problem they are based on e.g. prime generation. This gives a public and private key pair.

In general, the key pair is certified (the public key is signed) by a Certificate Authority to bind the key pair to some entity and convey that it is trustworthy.

Distribution

Key are distributed to their install locations.

For asymmetric keys, it may be either the private key ( Confidentiality-Integrity-Authenticity required) or the public key (Integrity-Authenticity) that is being distributed.

Usage

Keys are now live and should be used per the Recommendations section above. See Data in Use section.

Re-Keying Operations (aka, Rotation)

Re-keying (that is "key change operations", commonly referred to as "key rotation") is done whenever a key is thought to be compromised (see key lifecycle diagram) or a key change is scheduled for compliance issues (e.g., because of PCI DSSv2) or the key has been used for too many encryption operations.

Working keys (those that encrypt the actual payload) usage should be limited. According to Steven Bellovin, a security researcher and CS professor at Columbia University in a post to a cryptography mailing list:

When using CBC mode, one should not encrypt more than 232 64-bit blocks under a given key. That comes to ~275G bits, which means that on a GigE link running flat out you need to rekey at least every 5 minutes, which is often impractical. Since I've seen Gigabit Ethernet cards for <US$25, this bears thinking about -- and while 10GigE is still too expensive for most people, its prices are dropping rapidly. With 10GigE, you'd have to rekey every 27.5 seconds...

For reference purposes, with AES you'd be safe for 264*128 bits. That's a Big Number of seconds.

Rotation can be done automatically as part of the protocol (or done separately):

- For symmetric keys, in the Financial industry, Derived Unique Key Per Transaction (DUKPT) is a key management scheme in which a new key is derived for every transaction. However, there's a limitation of 1 million transactions per device, so a new key (IPEK) must be installed then.

- For Asymmetric keys, Ephemeralmodes where the asymmetric keys are changed per use; e.g. for TLS TLS_DHE and TLS_ECDHE.

Generally, when performing re-keying operations, all new encryptions are done only with the new key, but the old key is retired and kept around for some amount of time to ensure that all previous data encrypted with that key can continue to be encrypted. If that data can then be re-encrypted using the old key, that old retired key can be destroyed, but for some off-line archived encrypted data, it may need to be kept indefinitely. Regardless of how long an old key is kept though, it should be marked in some manner to indicate that it henceforth should never be used for any new encryption operations.

Backup and Recovery

The highest level keys in a system should be backed up to allow for recovery in a Business Continuity or Disaster Recovery event.

Revocation and Destruction

Symmetric Keys are generally used by 2 parties only so the revocation is generally done by changing to a new random key.

A Public key Certificates could be used by many so each user needs to be informed of the revoked status. Public key Certificates can be revoked using Certification Revocation Lists or Online Certificate Status Protocol or can be permanently removed manually depending on the environment. This prevents another entity using this public key for encryption or authentication as the certificate is revoked.

Archive

Keys are no longer in active service but are retained for validation or until it is ensure the key is no longer needed.

References

- http://www.keylength.com/

- Alfred Menezes, Paul van Oorschot, Scott Vanstone, Handbook of Applied Cryptography, 1997, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. (Online: http://cacr.uwaterloo.ca/hac/)

- Neils Ferguson, Bruce Schneier, Tadayoshi Kohno, Cryptography Engineering: Design Principles and Practical Applications, Wiley Publishing, ISBN 978-0-470-47424-2

- NIST Special Publications 800-57, Recommendation for Key Management – Part 1: General (Revision 4). (Online: http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-57pt1r4.pdf)

- NIST Special Publications 800-57, Recommendation for Key Management – Part 2: Best Practices for Key Management Organization. (Online: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-57/SP800-57-Part2.pdf)

- NIST Special Publications 800-57, Recommendation for Key Management – Part 3: Application-Specific Key Management Guidance (Revision 1). (Online: http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-57Pt3r1.pdf)

- ENISA (editor: Nigel P. Smart), Algorithms, Key Sizes, and Parameters Report: 2013 Recommendations, (Online: http://www.enisa.europa.eu/activities/identity-and-trust/library/deliverables/algorithms-key-sizes-and-parameters-report)

- http://www.cryptopp.com/wiki/Authenticated_Encryption

- https://cryptocoding.net/index.php/Coding_rules

Contributors

Authors

Kevin W. Wall / Chris Madden / Michael Howard

Reviewers

Candidates:

- Tor Erling Bjørstad [email protected] (offered via [email protected] mailing list)

- Jeff Walton – probable; need to ask

- Michael Howard? (ask; previous author)

- Chris Tidball (volunteered)

- Kevin Kenan? (ask)

- Anthony J. Stiebler? (Wells Fargo, ask)

Endnotes

[1] This is, after all to be a chapter on cryptography, and not a book about it. That and the fact that this chapter author is just running out of gas. If you are interested in such topics, check out the listed references.

[2] In Java, if you use DESede and do not specify a key size, you will end up with 2-key triple DES rather than 3-key triple DES. Note also to use 3-key triple DES in Java, you must have the Java JCE Unlimited Strength Jurisdiction Policy Files installed; otherwise, you will get an exception when you try to generate or use a 168-bit (i.e., 3-key) encryption key.

[3] Again, this is a chapter on cryptography, not a book. The interested reader should see Menezes, et al mentioned in the References section.

[4] A chosen plaintext attack (CPA) is a cryptoanalytic attack whereby an adversary has the ability to choose which plaintext he/she wishes to have encrypted along with the ability to observe the resulting ciphertexts. See the Wikipedia "Chosen Plaintext Attack" article for further details. If you prefer something with more technical depth, try CPA slide desk from the CS Dept of Wesley College.

[5] In fact, according to Cryptix co-author, David Hopwood (see http://www.users.zetnet.co.uk/hopwood/crypto/scan/ca.html) suggests that other cipher modes may not even make sense for asymmetric ciphers. Hopwood states:

Where an asymmetric cipher requires an encoding method in order to be specified completely, the naming convention is "encryption-primitive/encryption-encoding". Some existing JCE providers

will accept the use of a block cipher mode and padding with an asymmetric cipher (e.g. "RSA/CBC/PKCS#7"); this is not recommended, and new providers MUST reject this usage. An encryption primitive name on its own (e.g. "RSA", as opposed to a complete encryption scheme such as "DLIES-ISO(...)") SHOULD also be rejected.

[6] There are three possible approaches to applying a MAC to ensure the authenticity of ciphertext. One is the MAC-and-encrypt, which the sender computes a MAC of the plaintext, encrypts the plaintext, and then appends the MAC to the IV and ciphertext. The second is MAC-then-encrypt, where the sender computes a MAC of the plaintext, then encrypts both the plaintext (and generally, the IV) and the MAC. And the third is the encrypt-then-MAC approach where the sender encrypts the plaintext, then appends a MAC of the IV plus ciphertext. Of these three mechanisms, only the encrypt-then-MAC has proven to resist known cryptographic attacks (when implemented correctly).

[7] See Dr. Rick Smith's course notes on key stream attacks (at http://courseweb.stthomas.edu/resmith/c/csec/streamattack.html) for a discussion of what can happen if this advice is not heeded. Bottom line: Make sure that you do NOT repeat the key / IV pairs for stream ciphers or block ciphers operating in a streaming mode.